I’ve never found much struggle in writing about myself. When people ask how anyone is able to do it, I must admit I feel like a serial killer. Our fears often make little sense to those who don’t share them. I used to be afraid of high ceilings, and remain petrified of any scenario in which I might be forced to dance in front of people. So it is with our braveries, too.

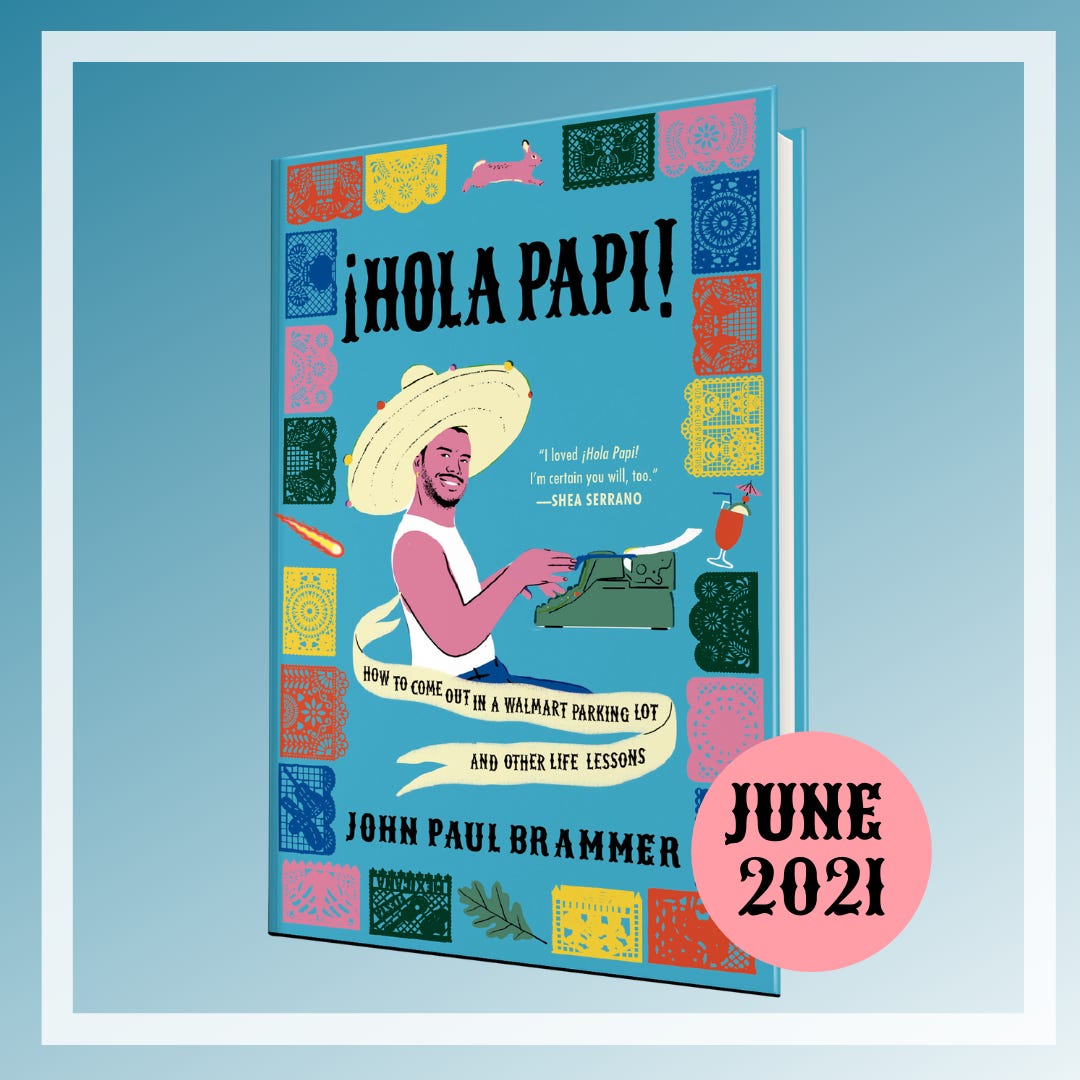

I’m not afraid in the least to reopen old wounds and share my pain with strangers. It’s less a matter of courage and more a matter of that office in my brain having never filled its desk by some happy bureaucratic accident. Still, in writing ¡HOLA PAPI! (the book), I’ve tinkered with this idea: Isn’t it a bit uncomfortable to share your most intense, most intimate experiences with a faceless audience?

The answer I’ve arrived at strikes at the central theme of the book. My reality, how I’ve come to understand this process, is that language is rife with shortcomings, and within its borders all I am able to do is conjure a portrait of memory, a photo of a photo of a photo.

“You’re young to write a memoir, aren’t you?” A taxi driver once told me (yet more evidence that I will say anything to anyone). It was extremely flattering and thought-provoking. There is this notion that the memoir, or memoiristic book, sets out to contain the author, to bring a sweeping life under the sovereign of language. Once read, the reader will “know” it, know the life, which is the subject. The idea that one must be old enough to write one hits at this: Your life’s story isn’t complete! You should wait!

In the book, I wrestle with the idea of authority, especially as it pertains to running an advice column: Who am I to be telling anyone how to live their life? It opens with me receiving a difficult letter and struggling with the idea of credentials. That’s chapter One. The entire book then becomes a sort of conversation with myself about the most key experiences I’ve dealt with up to that point—being abused, coming out, being sexually assaulted, falling in love, unlearning many of the things I had been taught—a life.

I take into account what I’ve learned from those things and how I’ve incorporated the lessons into my personhood, with the very last question being: Right, so, all that being said, are you indeed qualified to give someone advice?

No spoilers, but what I’ve come to understand is that the human is an animal hungry for narrative. Just about everything we do involves storytelling. My book is less a “here’s my life story” and more of an undoing of that life’s story and finding freedom in the notion that, yes, these events that have held such influence over me largely exist, primarily exist, as stories in my brain. Memory is an act of invention, not perfect recollection.

I think moral authority works in much the same way. It’s a nebulous, shifting thing, and we all have it in degrees depending on how someone else sees us, the narrative another person builds around us as it relates to their own. This is all terribly high-minded for a book with a chapter titled “How to Describe a Dick.”

A memoir is a composition. It is arranged into peaks and valleys to sustain interest and enhance the reader’s experience. It is curated. It is music, art. It is not fact, though rooted in fact. It is not “my entire life, presented to you.” Does that mean it’s false? No, not at all. I find it incredibly genuine and even quite beautiful. Is it always pretty? Not even usually, but that’s why I like it.

There’s plenty of scandal and spoiled loves and, I promise, humor in the pages. But what I’m getting at is that the book is those things before it is anything else, before it is “about” my life or is a laundry list of things I have experienced. I have something to say about memory, about the narratives we build to understand ourselves, and about the agency we have over those narratives even if we aren’t aware we have it.

It is, in the end, a story. And when it comes to stories, we have a great degree of authority over how we tell them and what they mean. What I hope to bring to you, along with the jokes and tears and shameful moments (there are many!), is the idea that in a world where it feels like we have so little control, we do have the power to make meaning for ourselves.

Thank you so much for indulging me here. You see, I really can’t spill too much of the actual book in this as that somewhat goes against the idea of publishing it (I must leave incentive for you to actually purchase and read it, which you can do right here).

I truly can’t wait for you to take it in. And of course, I remain eternally grateful to those of you who have subscribed to my newsletter and read ¡Hola Papi! over the years. I think people’s attention is the most precious thing, it’s worth so much, and it’s neither guaranteed nor owed.

So, mil gracias.

Con mucho amor,

John Paul Brammer

absolutely can’t wait to read, immediately preordered 😍😍😍