Your paid subscription supports my creative projects and allows me to pursue original essays and artworks like these. If you’re already subscribed, I hope you’ll consider upgrading to a paid subscription! Thank you for reading.

I won’t lie to you. Some aspects of my assessment of a group I’ll call “the AI art bros” come down to little more than personal vitriol based on vibes. Outside of any nuanced intellectual inquiry, I think of these people as sad little nerds obsessed with things like “productivity” and “startups” because they lack the curiosity, imagination, and bravery to humble themselves before the grand mystery of life, choosing to forego its complex pains and delights in favor of a pathetic illusion of control. They are lower than worms, in my view.

I felt I should disclose this.

For those of us who have wasted a considerable amount of time learning “how to draw hands,” the recent proliferation of AI art on social media, mostly spewing forth from various Twitter users with blue verified badges, can feel like an invasion. My goodness, we artisans might say, the smarmy suits and their robots are breaching the gates!

Such individuals, though, have never truly been too far afield from the Art World, which has long been a playground for the rich. I run the risk of positioning myself as precisely the kind of snobbish aficionado these people resent here, but I feel comfortable in saying that the AI art set’s appreciation of art relies heavily on capital and exclusivity. “Art,” for them, isn’t a medium for expression, but a frontier for conquest, property, and ownership. Things that, unlike profound meditations on the human condition, they are extremely interested in.

This is nothing new. Much has been written about western art’s relationship with capitalism. One of the most important, formative books I’ve ever cracked open is Ways of Seeing by art critic John Berger, which delves into among other topics the history of European oil painting.

“Oil painting, before anything else, was a celebration of private property,” Berger said of the much revered pieces (many of which, I revere myself) depicting aristocrats surrounded by their status symbols. “As an art form it derived from the principle that you are what you have.”

He also spoke of the art world’s concerted effort to imbue certain works with market value, a process that, to my mind, is reminiscent of the minting of NFTs, particularly of the Bored Ape variety. “The bogus religiosity which now surrounds original works of art, and which is ultimately dependent upon their market value,” he said, “has become the substitute for what paintings lost when the camera made them reproducible.”

Berger pushes past the visual beauty of individual pieces to expose an obfuscated truth: art, however neutral it might seem on face value, has an agenda, and that agenda will often reflect the dominant economic system in the environment in which it was made.

Aha! A stalwart AI art defender might say upon reading Berger’s quote. The camera was a new technology that, in a way, became a great equalizer. Value was concocted for original works to counteract the democratizing effects of photography and image replication. Isn’t this reminiscent of the backlash to AI art generators?

Well, no.

The problem isn’t so much the existence of the technology, but the approach to art its advocates encourage, and the culture they’re building around it. There are plenty of examples to choose from, but for our purposes I’m going to go with a recent Twitter thread that attempted to answer a question no one asked: What does the rest of the Mona Lisa look like?

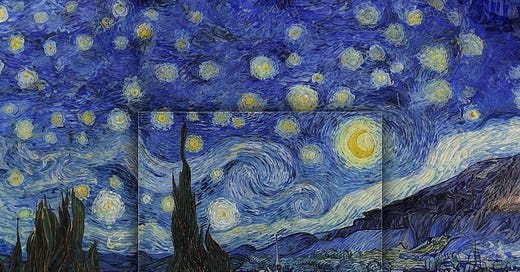

Using Adobe Firefly, the Twitter user, Kody Young, asked AI to expand some of the world’s most famous paintings, including Van Gogh’s Starry Night and Edward Hopper’s Nighthawks. One could be generous here and say that Young was simply playing with a new toy. He never asserted that he, himself, is an artist, or that these images represent some kind of improved version of the originals.

But I’m not feeling generous. While I’m not looking to bully Kody Young, specifically (I’ve never met this Young Man™), I think we can look at some of the egregious language he employs in this thread and use them as prompts for discussing broader cultural phenomena. Specifically, the language in this thread speaks to how a certain kind of tech person talks and thinks about art.

It’s important to note that these people come to us from a digital cave I call HustleNet. Here, tips are shared for how to better optimize your waking hours to generate maximum profit and CEOs openly discuss new and exciting ways to overwork or fire their employees. HustleNet is sort of like what would happen if LinkedIn did coke, but not in a fun way.

Ultimately, what the hustle mindset boils down to is to see in all things the singular quest for absolute mastery. Life becomes a matter of overcoming the hurdles in the way of accomplishing this. Mastery over every minute of your schedule. Mastery over your professional, personal, and romantic relationships. Mastery over yourself.

Time is a problem to be solved. Emotions are a problem to be solved. To overcome these obstacles is to achieve your final form as the ultimate landlord, of sorts, a cosmic landlord whose every hour, minute, and second are utilized to their utmost potential. Every experience must enrich them personally in some way, or it is a waste. Every relationship is mined for all it’s worth. This is the impossible finish line at the end of the grind.

Back to Young, who begins his thread with, “Ever wonder what the rest of the Mona Lisa looks like?” The key words here are “the rest of.” To people operating with this mindset, we, all of us, have been given a limited dose of Mona Lisa. Our girl La Gioconda was holding out on us. There is more Mona Lisa to be had, and AI can help us access that which has until now been kept from us.

Completely erased from the universe of this Twitter thread is Leonardo da Vinci. His existence would trouble the physics of this little world, which sees the Mona Lisa as a resource, one that the original artist was able to obtain some of, but we are able to get more of, through the enhanced abilities of technology. The Twitter thread understands the Mona Lisa not as a work of art with intention behind it, but as something more akin to petroleum or gold.

Young does this again in the second tweet in his thread with Starry Night, while also incorporating a second, slightly different horrifying thing. Again, as with da Vinci, there is no Van Gogh here, whose painting depicted his view from a sanatorium. What is present is a rather disturbing use of the word “original,” referencing some other person’s AI-expanded version of the painting, a person who is name-dropped where Van Gogh was not.

I just decided I don’t like you either, Lee Brimelow.

In any case, while it could be said that Mr. Young isn’t a great representative of his ilk, I see in this thread a general trend that unnerves me about the culture that’s sprung up around AI art, a culture that thinks of art in much the same way that it thinks of real estate, a culture that is primarily concerned with how to turn even more things into real estate, real estate being the only concept of interest to these guys.

It’s the optimization of art in a culture where art is understood as a resource to be exploited. The fact that these famous paintings have finite boundaries, that they end, is a problem to be solved. You know what would add value to the Mona Lisa? More Mona Lisa. You know what’s better than Starry Night? An even bigger Starry Night.

It’s no wonder that the AI art crowd has little respect for craft. It takes a lot of time to get good at drawing. AI can streamline this process, cut out the middleman, so to speak, and bring us directly to the desired results. Time is money, after all, and heaven forbid we waste a single second of it doing things a computer could do for us.

Never mind the quality of the result, there is deep sadness in this way of thinking (these are people who will never know the joy that failure can bring, the happiness, for example, of drawing for the first time a human hand the way you’ve always wanted to, but couldn’t, because up until now you hadn’t given proper attention or respect to the small spaces between fingers, a tiny revelation not only for your own work, but for your understanding of the anatomy of the human body, your body).

The central question when it comes to AI art so far has been, “is it art?” In my opinion, as things stand right now, no, it’s not. It might surprise some people to hear that I think AI could be a tool for artists. Artists have always feared, celebrated, rejected, and embraced new technology. That will likely always be the case. But I don’t think this is the most important factor at play here.

I think AI art as it’s commonly being used at present bolsters the worst elements of art that existed before the technology was invented. Many of its prominent advocates see art as another medium for property and profit, and artists as a problem to be solved. The fact that there is effort, labor, and an emotional toll behind paintings is an issue that can be streamlined, if not worked around altogether.

AI could get even better, at least aesthetically speaking, at churning out expanded versions of the famous paintings presented in this thread. With time, this is all but inevitable, which is why I tend to avoid criticisms of AI art that amount to little more than “it doesn’t look good.”

But for now, the images generated reflect the philosophical and moral vacuousness of their champions: empty space, masquerading as improvement.

My internet sleuthing skills are not slick enough to find and verify this, but as a teenager I recall seeing an Andy Warhol piece in a museum that was two canvasses side by side. One had a composition and the other was just a solid color, and there was something about how he’d only added the 2nd solid color painting because it would double the value of them as a set. Anyway all this reminds me of that!!

This went so hard ☠️